Beyond the binary in AI Leadership

Updated on

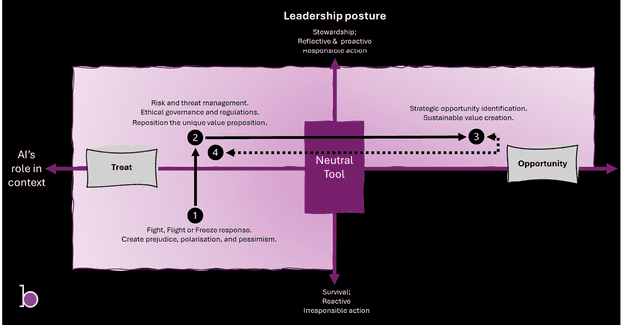

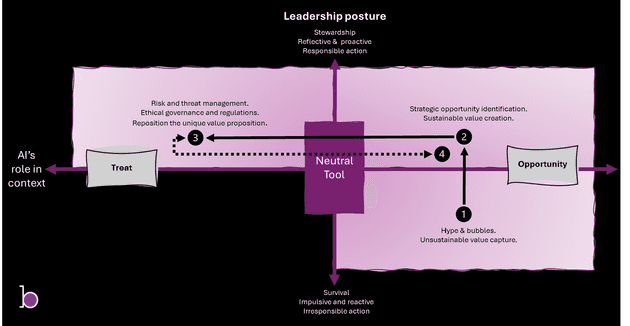

Depending on who you ask, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is often framed as either the most incredible opportunity of our age or the greatest threat to civilisation. I believe that reality is more subtle and therefore more demanding of leaders: AI is neutral. The impact AI will have on society is directly shaped by the consciousness leaders bring to each decision. Our decisions reflect our values and the vision we hold for humanity's future. Ultimately, it is through these choices that we determine whether AI becomes a force for collective benefit or harm.

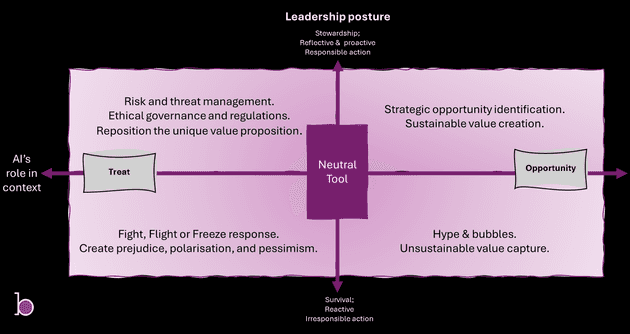

The developmental framework presented here signposts a shift in leadership perspective: from “either/or” to “both/and”. I believe this shift is a critical prerequisite for leading with integrity. The value of this shift is vertically developmental: it expands a leader’s capacity to hold complexity, embrace paradox, and respond with wisdom rather than reaction. Being vertically developed in the age of AI enables leaders to navigate the disruption and steward systems responsibly.

AI's role in context

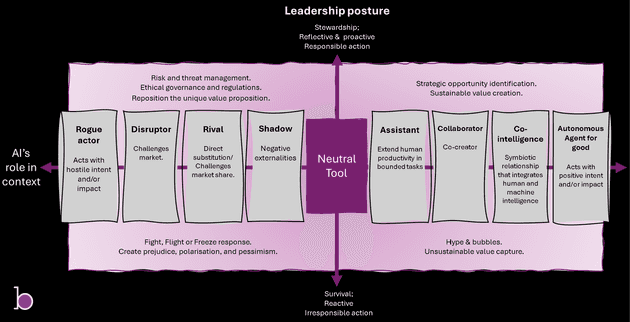

The first dimension, on the horizontal axis, illustrates the various roles AI can assume in society in relation to humans within a specific context. On the threat side, AI appears as a shadow, competitor, disruptor, or rogue agent acting against human interests. On the opportunity side, AI appears as an assistant, collaborator, partner, or autonomous ally working for the common good. Recognising that AI is simultaneously deployed across various explicit and implicit roles is essential. This is the development edge.

Consider the media industry: AI tools are being deployed, with the positive intent of enabling content creation at lower cost and greater speed. On the opportunity side, these tools act as assistants and collaborators, expanding creative capacity and lowering barriers to entry. Yet, these tools also cast a shadow in the industry as they amplify the creation of misinformation. Additionally, market forces converge to intensify competition with traditional content creation business models. Going further still, as automation increases, the industry’s core value proposition begins to be challenged.

This example illustrates that even in narrowly defined settings, AI can be deployed into multiple roles. The role AI assumes in a specific context may not always be in a leader's control. How one leader deploys AI in one context may cast a shadow, showing up as a threat for another leader in another context.

Furthermore, beyond unintended consequences, some leaders may choose to deploy AI with malicious intent. Building on the media industry, the deployment of tools that enable the generation of non-consensual “face-swapped” pornography raises profound ethical concerns.

Building on the HARI framework

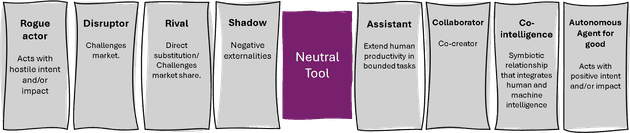

I want to credit Deidre Morrison and her HARI framework for inspiring the horizontal dimension in the framework proposed here. Her HARI framework is already used in many organisations to help navigate anxiety about AI.

As Einstein said, “Everything Should Be Made as Simple as Possible, But Not Simpler”. My criticisms of the HARI framework in its current one-dimensional form are that it may imply that being an AI-optimist is more effective/efficient than being an AI-pessimist. This invites introjection: “AI is (only) good!”. I believe this is a dangerous oversimplification that ignores the systemic implications of AI. I attempt to add a vertical developmental lens to the HARI framework. I believe this moves us beyond the binary towards a more nuanced and deeper conversation about AI. I think embracing a systems view is tremendously vital if we are to responsibly create AI’s role in our society while also protecting the integrity of our society.

Leadership posture to AI

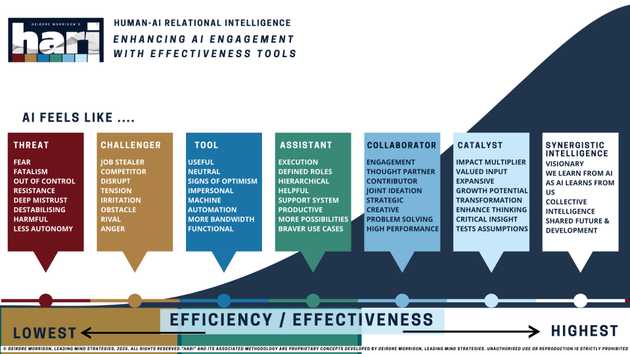

Today, not all leaders approach AI in the same way. The second dimension of the framework, represented on the vertical axis, captures a leadership posture. At the top sits conscious leadership. Conscious leaders are reflective and proactive; hold opposing perspectives, they name trade-offs, and purposefully navigate complexity as stewards. At the bottom sits unconscious leadership. Here, leadership collapses into impulsiveness and reactivity. Leaders who operate from this posture are often trapped by their ego-driven instinct (fear or desire response). This axis represents a leader's vertical development 1.

The Four Quadrants of Conscious AI Leadership

Once we map AI’s role in context against leadership posture, four distinct patterns of response emerge. These quadrants move us beyond how leaders perceive AI to how they choose to act in relation to it. Each quadrant represents how a leader may take action to shape not only organisational outcomes but also broader societal impacts.

Unconscious Threat Response

A leader who perceives from this perspective often has a fight, flight, or freeze response. Fear drives prejudice, panic, and pessimism. Trapped in this, the leader abdicates his responsibility for co-creating AI toward just, equitable, and inclusive outcomes. A leader operating from this perspective fails to acknowledge the potential benefits of AI, and by extension, fails to negotiate equity for themselves and those they lead in these benefits. Because the leader's worldview is polarized, the leader acts in a polarizing way, creating polarized outcomes.

Unconscious Opportunity Response

Hype, FOMO, and trend-chasing dominate intentions. The desire to capture value narrows the leader's vision and prevents them from creating sustainable value2. Leaders fuel bubbles when they chase trends without the critical thinking needed to move from high-level strategy to disciplined execution. The real challenge of change management is also ignored. Leaders operating from this posture fail to address systemic consequences; they don't stop to consider the repercussions of their actions on the broader ecosystem, nor do they take responsibility for them. In doing so, they jeopardise the integrity of the organisations, communities, and societies they are called to serve.

Conscious Response

A leader who is vertically developed has the capacity to hold opposing perspectives simultaneously. Here, leadership expands to perceive the world with greater complexity allowing the leader to recognise the opportunity and the risk. Instead of being compelled to adopt a fixed perspective, she dynamically operates across the upper two quadrants depending on context. This increased capacity enables leaders to recognise AI as a metamorphic force whose risks and opportunities shift as its influence moves across contexts and within broader systems.

She actively manages threats and risks. She harnesses direct dangers and threats as pressure to evolve. Competition and challenge are framed as welcome catalysts for inclusive reinvention. She resists being swept up by industry rhetoric and prioritises long-term, sustainable, and strategically aligned value creation. She is actively managing trade-offs as she strategically and analytically navigates through the complexity.

A conscious leader recognises that her fiduciary duty extends beyond the direct management of her strategic and operational risks; the resilience of her organisation is deeply correlated with the strength of the communities in which it operates 3. This acknowledgement translates to a clear point of view on related systemic issues, and she encourages participatory debate to inform governance, safeguards, and ethical guardrails4.

Additionally, regardless of what happens at the macro level, disruptive change invariably results in both winners and losers at the micro level. The conscious leader honours that by being empathetic and compassionate in how they discuss AI; otherwise, they participate in co-creating a polarising society.

Developmental example 1 - Unconsciously pessimistic

Frame (1)

A headmaster bans AI, convinced it will destroy academic integrity. Students turn to hidden use, teachers double down on policing, trust erodes, and relationships polarise.

Reframe (2)

Months later, the headmaster concedes AI is unavoidable. Students, teachers, and parents collaborate to create guidelines for responsible use. Through participatory governance, trust is rebuilt, and academic integrity becomes a shared responsibility among all stakeholders. Assessment shifts from rote recall to projects blending AI and human intelligence. Soon, other opportunities start to emerge.

Expand (3)

AI is recast as an invitation for deeper inquiry into the human condition. A program trains teachers and students to work collaboratively with AI to enhance learning outcomes. Critical thinking and a broader perspective of human intelligence are emphasised as the new differentiators. Use cases to support teachers' effectiveness and efficiency are actively pursued. For example, sector-specific tools that place a strong emphasis on fact-checking and cross-referencing are deployed to help teachers develop rigorous lesson plans. With trust restored, the school begins piloting an integrated AI classroom assistant, tightly embedding AI in the classroom alongside human teachers.

Bridge (4)

When students and teachers enhance their ability to navigate misinformation, the benefits ripple through the local community. The school expands the curriculum to foster dynamic and participatory learning with an emphasis on soft skills and practical life skills. Fear evolves into stewardship. The valid fear of job displacement among teachers and assistants is acknowledged and intentionally addressed. Not only do teachers secure equity, but their role is also refocused to attend to the inner development of young people. The school becomes a model for human-centric education, advancing both local trust and the greater good of society.

Developmental example 2 - Unconsciously optimistic

Frame (1)

Executives deploy autonomous AI into business processes without proof of concept or proper tool analysis, thereby removing bottlenecks. Oversight often disappears, leading to an increase in business process errors and widening compliance gaps. Employees grow fearful and resistant, some act maliciously, and trust collapses.

Reframe (2)

Regulators intervene, forcing reflection. Executives acknowledge AI as both an opportunity and a threat. Transparent and participatory governance structures are established, with a strong emphasis on human oversight and accountability. AI is applied selectively, with a focus on observability, traceability, and repeatability.

Expand (3)

Resistance is recognised and honoured. Leadership commits to maintaining employee equity during AI transformation. Trust begins to rebuild, and oversight strengthens. AI adoption deepens as employees become engaged in shaping how autonomous agents are utilised. Equity becomes a competitive advantage as workers channel creativity into co-designing AI-enabled processes and products..

Bridge (4)

What began as hype matures into stewardship. The AI transformation addresses deeper cultural issues within the organisation, including accountability, discipline, and shared standards. By holding risk and value together, the organisation becomes both strategically sharper and operationally stronger. It emerges as a model of responsible AI adoption, earning brand trust and shaping industry-wide standards for human-centric innovation. Executives are recognised globally for their balanced thought leadership in responsible AI and intentional influence in reducing systemic risk.

The leadership imperative for conscious leadership

While many leaders recognise the need to mitigate risks that affect financial and operational outcomes, authentic, responsible leadership requires a broader perspective. What sets conscious leadership apart is a deeper stance of interconnectedness. Conscious leaders view themselves and the organisations they lead as part of a living system that encompasses both people and the planet. Conscious leaders acknowledge that risks are interconnected across systems and that leading in a system demands that they expand their leadership agenda to include Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors (the third bottom line).

Conscious leadership is about owning systemic risk in the service of the integrity of the entire system. AI demands a conscious posture,

- When AI poses a threat, conscious leaders do not simply defend their moat, they reinvent the basis of competition.

- When AI is enabled, conscious leaders resist hype and strategically realise long-term sustainable value.

- When AI polarises, conscious leaders rise above binary thinking and navigate the paradox.

Ultimately, AI serves as a mirror, reflecting our consciousness to us. The leadership challenge is not to choose sides but to lead in ways that honour interconnectedness, reinforce love-centred values, and align with our highest purpose. The question is not "Will we fear AI or embrace it?” Instead, the question is: “Can we lead consciously enough to co-create a future where AI serves our shared good?”

Footnotes and references

Footnotes

-

Nick Petrie (Center of Creative Leadership) describes vertical development in an accessible way. See Part 1 and Part 2. ↩

-

Differentiating between capturing value (an extractive mindset) and creating value (a generative mindset) is essential. From a developmental perspective, this represents a shift in locus of control from external to internal, from being a pawn to being a player, from being a game taker to a game maker. ↩

-

My argument here is grounded in a broad fiduciary duty to stakeholders, not just shareholders. I would, personally, however, also argue that even taking a narrower view of fiduciary duty would be ground enough for a strong point of view on systemic risk. Towards Accountable Capitalism: Remaking Corporate Law Through Stakeholder Governance. ↩ ↩

-

All systemic issues are related; this is why we call them systemic. For example, there is a strong interlink between Artificial Intelligence and the drivers of climate change, as well as between Artificial Intelligence and the drivers of geopolitical tensions. ↩